*Disclaimer: this is not intended as a purely instructional article on the growing of tomatoes. For more information on the growing of tomatoes and the processes and techniques we use, reach out through our instagram: @goodworkgardens

There is no gardening achievement quite like the tomato. Often undertaken by absolute beginners and professionals alike, they are a symbol of the health of the garden as well as a motivating image of the harvest one must get to at the end of the season.

When we started growing our own tomato plants four years ago, we made every mistake you could possibly make. In starting seeds, we simply tossed them into some random containers of soil, put them in a humid plastic container and set them by the window to give them some light. We saw sprouts after a couple days. They quickly shot up, reaching weakly for the light of our window, then fell over with their spindly stems and died, pale and desperate. Enter: our neighbor.

A horticulture student at our local university, she had the magic touch. She looked at our setup in disbelief and said three things that changed our routine.

- Put their light as close to their container as you can. We bought a long grow-light from our local hardware store and set it about two or three inches above the soil surface. When they sprouted and as they grew, we kept raising the light with them.

- Use starter soil. It made a huge difference in both nutrient content and moisture retention. The soil was loose enough for little seedling roots but could also retain moisture so the sensitive sprouts would not dry out.

- Put the seeds near the surface and cover them with vermiculite. We had been burying our seeds about an inch below the surface and leaving the soil uncovered. We consistently had gnats in our grow area (our living room). The vermiculite increased our germination success as well as got rid of our gnat problem.

With her help, we kept learning from our mistakes and kept growing. When the seedlings started getting tall, we called for her help again. She recommended we keep a fan on them to build the strength of their stems. The little breeze signals to the sprouts to “Hold on!” and this develops their roots and stems.

In those years, we were container gardening in our inhospitable yard. We planted our tomatoes in an assortment of five gallon buckets along our fence and supported them with flimsy tomato cages that are common in gardening centers. When we began to get ripe tomatoes, we were elated. Almost immediately, we understood why harvest festivals have been such an integral cultural practice in every civilization in the history of the world. Harvests seem impossible. That is why they are celebrated with such devotion. The work and attention and endless variables throughout the season distract you from the possibility of a reward. When you finally get to that day, it feels unrelated somehow, and providential.

In that year, I think we had somewhere around five pounds of tomatoes and random assortment of other produce – chamomile flowers, a couple shriveled radishes, four or five little potatoes. Still, we were hooked.

The next year, in addition to the container garden in our yard, we also signed up for our local community garden where we were assigned an in-ground garden plot of one hundred square feet. We took the lessons that we learned the previous year and we were off to the races. And we did much better! It was nothing compared to what we do today or compared to professionals but we were increasing our yield and gardening in the actual ground. We learned to bury the tomato starts deep, to mulch heavily, and to KEEP UP WITH THE PRUNING!

We were still not measuring our yield yet but I estimate we got about ten pounds of tomatoes and maybe a pound of peppers and carrots. Often we would neglect the plot, getting busy and distracted in our day-to-day lives as one does, and we would forget to water.

After two years of consistent learning, lots of trial-and-error, and becoming more attentive to the garden, we were really becoming skilled. That year, we started close to five hundred plants and sold them in a little street market sale on our street alongside our neighbors. They were all happy and healthy. We had three neighbors who were horticulture majors or professional gardeners and that helped with increasing our knowledge. It also happened to be a wet spring and summer. Our community garden plot exploded with life and it seemed like we did not have to try as hard to get ten times the amount of produce.

Overwhelmed with the abundance, we began to keep track of our harvests in poundage and type of produce. By the end of the season, we had raised one hundred pounds. Tomatoes, beans, carrots, squash, peppers, radishes, and many different types of herbs. That year changed things dramatically – we finally saw the potential in raising quality food for ourselves and others, a dream which still drives us currently.

The community garden and our haphazard container garden weren’t cutting it anymore. Our ambition was to do even more and for that we needed more space. I connected with a local who rented his land out. We didn’t need much. We had only managed a hundred-square-foot plot and a few buckets, so we didn’t want to scale up faster than we could handle. After much initial work, we set up three hundred square feet of in-ground gardening space and a coop full of beautiful chickens. That year we grew approximately three hundred pounds of produce and gathered something around 2,000 eggs.

That year we had grown twenty tomato plants. Fifteen made it to harvest, the others dying of various causes including disease and pests. Tomatoes come in so many shapes, sizes, and colors, we wanted to experiment a little and find out what the best varieties were. Our personal favorites were the German Pink and the Pineapple for cutting tomatoes, the Peron and Roma for sauce or salad tomatoes, and the Prairie Fire and Yellow Pear tomatoes for snacking/cherry tomato varieties.

Following the tomatoes from seedling all the way to a favorite recipe was deeply rewarding. There is so much to say about this staple crop in its impact on cuisine and culture but that is for another time. For now, I will focus on the growing… and the killing of tomato seedlings.

This year went a little different than previous years. Here I was, thinking we had this all figured out and down to a science. I thought we could grow a thousand seedlings with our eyes closed. But each year teaches you a different lesson. Each year the circumstances are different, the variables have changed, and you are not the same individual that grew this garden the previous year. It is never the same garden twice.

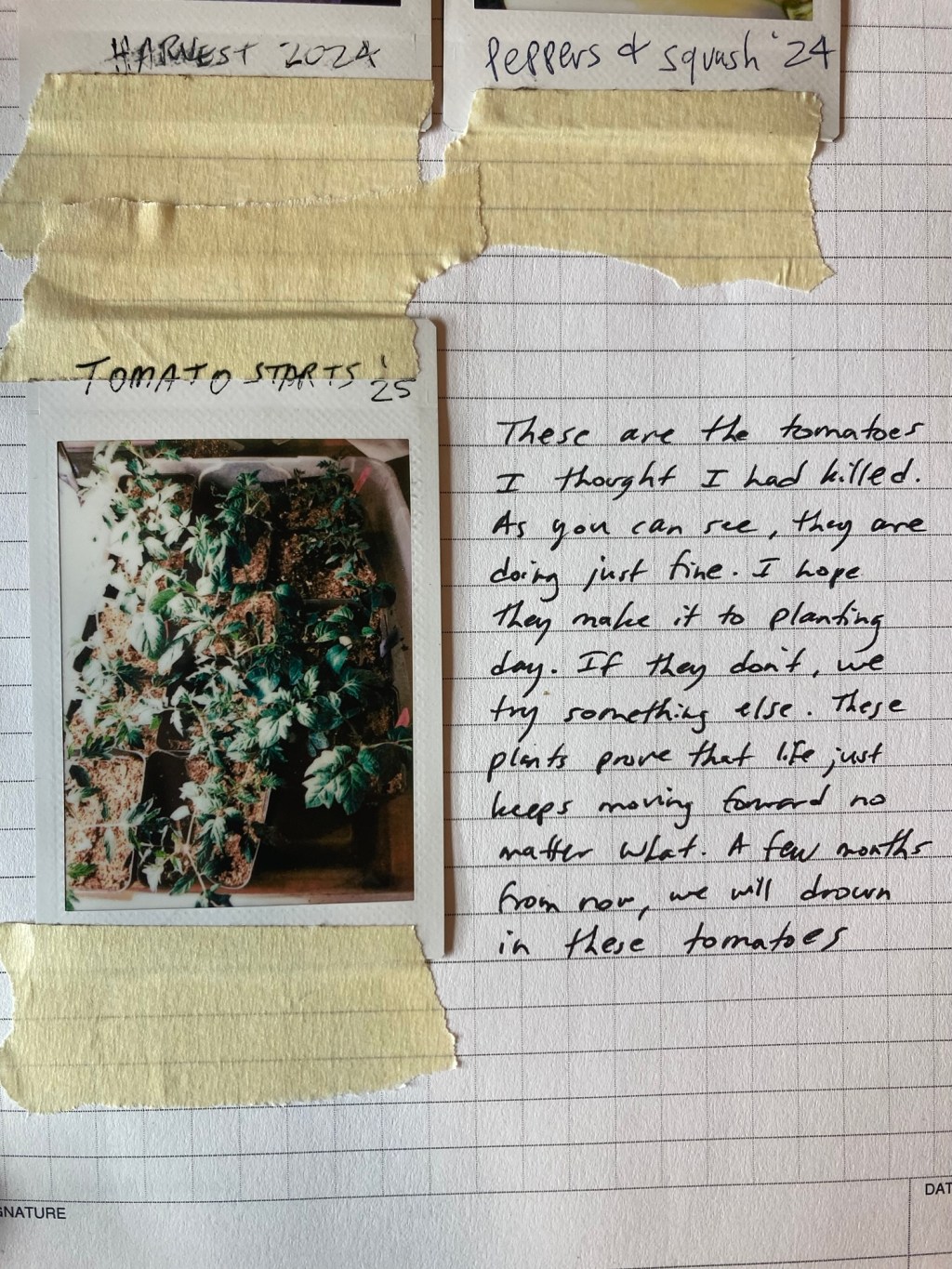

Of the one hundred tomato plants we started, almost all were withering and dying after the first two weeks of growth. I stressed about the different variables – the soil quality, the watering schedule, the lights we used. Making adjustments seemingly changed nothing. They just kept on dying. A last ditch effort was made and we potted up the little, fragile seedlings to see if the new soil would help them take hold. The hundred seedlings were soon down to twenty-five of the healthiest specimens and we had to compost the rest. I watched them diligently, hoping they would somehow make a rebound before the planting day.

After just two days, they grew in leaps and bounds. I thought I had killed them. I thought I had pushed them to the absolute limit with neglect. But that little mite of life was still crouching inside them, waiting for the chance to spring back.

Gardening always surprises me in this way. I suppose that is the message of this particular post. The resilience and potential of life in all respects seems unfazed, undeterred.

This post isn’t about how to grow tomatoes, it’s about how to kill them. We are always good at that part because it is easy. The path we have taken toward growing hundreds of pounds of produce is littered with the trial-and-error plants we have killed along the way. Each year we kill more tomato plants. Each year we end up harvesting more than we did the year before. The dead and dying plants are evidence of effort, a testament to our attempts. And that is what people must do: fail all the way to success.

You look at your collection of withering seedlings on the shelf and you think it’s over. You visit your garden beds and the grasshoppers have helped themselves to everything but the bare stems of your herbs and tomatoes. Dejected and hopeless, you are ready to give it up. But some part of you still clings to that image of the harvest at the end of the season. You’d like to give up and go home but you make one last push. Always that last effort. You keep going, you keep working.

A half dozen farming phrases, dripping with stoicism, come to mind. “Oh, well.” “Tomorrow is another day.” “Moving right along.” All of them mean one thing. Just keep going.

The leaves are stripped and brown in the sun but you keep watering the beds anyway. The seedlings could not look worse but you pot them up anyway. It may be stubborn persistence or stupid hope but you keep doing the work in spite of the conditions. Somewhere along the way, that mite of life catches and you’re walking through the lush and abundant world that seemed impossible not too long before.