If we conjure up the image of a plain, manicured lawn, chances are there is no room for anything else. There are typically no other bugs, animals, or plants that can coexist within a perfectly manicured lawn. Only that one type of grass, that one length of each blade, perhaps even a sign that says to ‘keep off’. In fact, there are concerted efforts to rid the lawn of anything that may inconvenience it or compete with it. Millions of dollars are spent each year on chemicals the average user is entirely ignorant of, being poured out on lawns, driveways, and sidewalks to spare us the sight of the rogue dandelion, to kill the insects, to preserve that uniform mat of green lawn.

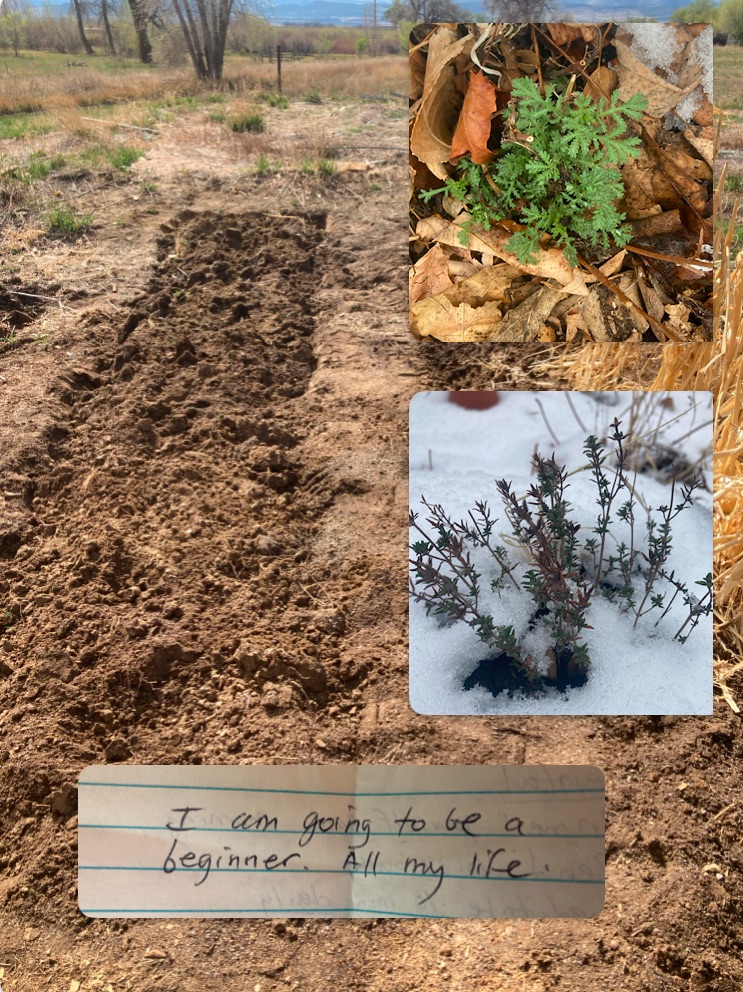

Now, if we conjure up an image of a healthy and abundant garden, we reckon with an entirely different world. In order for it to be abundant and productive, we imagine there to be many different plants, many different insects, and a general happening of all with all, everything mingling together in some complex system we can scarcely understand. The beginner gardener starts out by learning that there are beneficial and harmful insects and they are careful not to be so enthusiastic about killing the one that the other is destroyed in the process. The intermediate gardener learns that there are even certain plants one can cultivate in order to attract the beneficial insects or repel the harmful insects. The advanced gardener knows that if they do their job well in organizing and arranging the garden for its health, then each will care for each and a certain balance will be attained that does not require their constant oversight or intervention.

The two images I have just described are examples of the difference in creating niches or encouraging ‘vectors’ of abundance. This is similar to the idea of placemaking in designing public spaces. These ideas, arguably, are mainstays of the best practices of goodwork.

A niche is that crevice, nook, or cranny of the world in which something can find its natural position. In ecological terms, a niche is a condition or environment in which a plant or animal thrives, encouraged to express its true nature. A vector is a directional magnitude that implies transmission, communication, or aim. I think of a niche as a corner of the world and a vector as all the possibilities that can pour out of this little corner.

A niche is a foothold, from which something can launch into full expression. And placemaking, in this instance related to goodwork and to gardening, is about cultivating many places where a niche could support life and where life could then support vectors of abundance.

Joel Salatin, a renowned farmer using regenerative agricultural methods, would refer to this practice as “Honoring the pigness of the pig, the cowness of the cow, or the chickenness of the chicken.” Each plant or animal has a nature which it most easily expresses in its particular niche. To honor that plant or animal is to create a niche that allows it to express its true nature.

The pig is a forager; it roots around with its snout in the dirt for morsels of food. The cow is a grazing ungulate, partial to herd mobbing on a diet of grasses and forbs. A chicken is an omnivorous scavenger, picking and pecking through seeds, grain, insects, and grasses. So, what happens when you constrain the pig, cow, or chicken to a tiny enclosure, with no access to soil or sunshine, feed it a diet far-removed from its natural inclinations, and otherwise expect it to produce abundantly? Well, you get two things, the image of the modern farming method and a slurry of disease, waste mismanagement, and low-quality food. One practice is about creating places, honoring a niche, and being a part of abundance. The other is about wanting abundance, mimicking abundance, but otherwise skipping the work necessary to be a part of its true nature.

This practice does not concern only natural environments or the components of animals and plants. It also has a great deal to do with how people relate to each other through the physical space they inhabit. Master sushi chef, Jiro Ono, is a great example of a craftsman with an eye for cultivating a place. His restaurant is like a niche in this way, which caters to a specific aim and sensation that he wants to communicate to his guests. It is a small and humble-looking restaurant, with only ten seats at a long bar-top. The lights are warm and low. The sparse design does not feel minimal or bare but sleek, clean, and harmonious. With a smaller seating arrangement, Jiro is free to cater to the guests based on his observations; do they eat with their left or right hand, what size sushi will they eat in a given time in order to keep the pace of the meal. And while the elegant simplicity of his place is felt deeply as graceful and easy, it is in reality built on many hours of disciplined work, attention to detail, and an attitude of mastery that makes Jiro desire to continuously improve his process over the years, even as he continued to work into his 80s, 90s, and now, having turned 100.

There are also countless ways to make a place or niche for people in one’s daily life. Your own home could be an example of a niche which you form yourself day after day with the habits you keep and the ideals you hold dear. Making a place for yourself can be an art, a practice. You can make it open and welcoming to others as well. Those who come to visit may marvel at some unspeakable quality your home has that feels inviting, warm, and encourages connection. It does not have to be filled to the brim with shiny knickknacks or gadgets, it does not have to be decked out with expensive furnishings and decorations. It merely has to have that perfected quality of a place that is made with intention and a mind for harmony.

Even something as plain as a conversation can be made into a place for stopping off, a place for resting, a place for an encouraging word or a supportive idea. How desperate people are in their daily lives for some sense of belonging or support that a conversation alone may be memorable enough to last them the year! Think of the last time you received a compliment, how long that impression has lasted. People can make places for each other in easy ways that make the process of routine actions more bearable and even beautiful. Letting someone go ahead of you in line, handing out compliments that come to mind, assisting someone in some dreaded chore. No task is so low that it cannot serve as a matter for our attention.

A farmer who raises cows does not actually raise the cow but tries to create an environment in which the cow cannot help but grow healthfully. A therapist does not give the patient right conduct, good thoughts, or healing but provides an environment of communication in which all of these things are allowed to develop of their own accord. Feed the birds, the worms, the bees and your garden will feed you with ease.

There is a subtle and indirect logic to this aspect of work, as opposed to the image of effort, skill, and discipline that is often conjured in the mind when thinking of achievement. There is a place for effort, skill, and discipline; these are indispensable things. But the indirect work of preparing a place may take you further, and with greater ease, than the repetitive and frustrated attempts to create something from willpower alone.

How to make a place, a niche.

Begin by organizing your corner of the world. This may sound bland or ineffectual. But you must remember that there are many people who seek to better the world by focusing on the weeds in other people’s gardens. This gets us nowhere. The people who succeed in making a place are those who do what they can, where they are. They plant a row of flowers, a native bush, they forego weed-killer or fertilizers. They help their neighbors rather than trying to save the city. That is oftentimes more heroic. This wisdom is handed down by Marcus Aurelius, a Roman emperor and practicing stoic. He noted how the insects put in order their little corners of the universe and kept the world going by doing the work that was natural to them. Our work may be drudgery sometimes; it may be joyful other times. But it is our work, and we continue to do it because we are helping to put together our corner of the universe.

Design it with a visitor in mind. When you set out to create a place for something or someone, you must keep them in mind in order to make it inviting. You wouldn’t try to make a place for a mouse the same as you would for a cat. Mice like little crumbs, dark corners, and quiet. Cats like cozy sunbeams, high perches. Cats like mice. We must take into consideration the nature of those we wish to see thrive and go about creating a place that is best for them. The cows like tall pastures of polyculture forage, not dry dirt fields covered in dung. Chickens like to scratch and peck, chase each other a little bit. You learn to fall back in love with observation. The situation you create will invite the most suitable visitors, not necessarily the visitors you want. So, you must become adept at observing what your most desired visitors want, dream of, cherish, are fearful of.

Be comfortable with silence. Silence in all its forms can create tension. Unanswered questions, untaken paths, an averted gaze. But constant noise and effort do not make the place, they simply make it uninhabitable. When you first make a niche, it may go unanswered for some time. You must keep the practice of cultivating this niche until your visitors find it. Practice silence and people will begin to tell you about themselves. The bees will come to the garden when the wind stops blowing. The water clears, the haze lifts, the situation becomes clear. Practice silence enough and you may even hear yourself again. Here’s a lesson from the worms: do your work in quiet obscurity and you will reform the earth.

Accept it, Expect more from it. It is okay that things are the way they are right now. It is also okay that you want to make them better. Both of these things can be negotiated in time and patience. If you do not accept how things are right now, you will never be able to function in your work. If a sculptor did not accept the hardness of the stone for what it was, they would never be able to work with it. Part of accepting something is accepting that it may be disappointing, or not all that it could be. It is a beautiful thing that someone can take a neglected or disordered thing and make it into a productive or useful thing. That is why we can accept something and also expect more from it.

Optimize the Unremarkable. We are drawn to herculean efforts, dramatic transformations, and fast turnaround times. When we do not get big returns, we are inclined to feel disappointed. This can also be called the lesson of compound interest. Small, incremental changes over time compound to create great change while short bursts of effort can leave us empty and fatigued. Kaizen, or continuous improvement, is a business term stemming from Japanese industries following World War Two, and it can be dissected as an entire philosophy unto itself. More on that later. But the point is to abandon the monumental task and focus on optimizing the unremarkable tasks. Of work, of life. How much better off would we be if we optimized our daily routine to get the best sleep we could? And the gardener who optimizes their soil health will find themselves far better off than those who optimize for straight rows.

Conclusion

There are many examples of places we can make for each other. The morning routine, the lunch date, the afternoon walk. The kitchen, the living room, the garden. The restaurant, the gym, the office. Each place should be regarded as something to be honored and treasured, as part of our goodwork and part of our daily lives. We can make it clean, make it easy to work in, make it pleasurable to share with each other. When you are finished exercising at the gym, you clean off the equipment and on some level you can say ‘thank you’ to that space for helping to make you stronger. When you are done with your dinner, you can thank your server and stack your plates neatly to be bussed. The clear delineations of ‘jobs’ don’t really matter here as much as the process of our goodwork, which belongs to the spaces we inhabit and not necessarily to specific people. Creating a place, cultivating a niche for yourself or for others, is about deciding what kind of world you want to live in. Would you like to live in a cleaner world, in a nicer world, in a more abundant world, in a more efficient world, in a pleasurable world? Good, me too. And we can do that by being clean, being nice, cultivating abundance, and bringing pleasure to people’s lives. In any manner of way, we can choose to do this each day.