Work is how we reconcile ourselves to our worlds, our surroundings, and to each other. Work is a natural process that unfolds in people as well as in other aspects of nature throughout all of time.

As such, we should probably deem it worthy of some respect and attention, right? Yet a Gallup pole shows that, along with dissatisfaction, workers also report high rates of disengagement and unhappiness.

60% of people reported being emotionally detached at work and 19% as being miserable.

50% of workers reported feeling stressed at their jobs on a daily basis, 41% as being worried, 22% as sad, and 18% angry. 33% reported feeling engaged.

Something is amiss if so many people report being unsatisfied with their work lives. People typically have working lives that span a period of forty years – age 25 to age 65, roughly. For those of us who started working in our teen years, that window of time is even longer. Would anyone want to spend that time feeling disengaged and unhappy rather than being engaged with meaningful work and productive behavior? So where is the disconnect, and what do we do to remedy these issues?

Goodwork is Natural

There is a misunderstanding about work, stemming from the definition we use to categorize work in the human sphere of activity. But if we look at the natural world for examples of work, we find it as common as the work we are inclined to do as people. The beaver goes about cutting logs and making dams. It is their home, and it is fundamental to their nature as beavers. In order to create it they must do good work.

This is the same as with the bird’s nest, the dung beetle’s dung, the dens of any number of forest critters. In order to connect themselves to their world, they each must do their work. Even the worm, the greatest little workman the world has ever known, creates a layer of soil fertile enough for the rest of life to function in abundance, and they do this work unassumingly beneath our feet, content to churn through the dirt in obscurity. The worm’s work is part of his existence, it is woven into the fiber of his being, and it builds the world which we stand on.

“If a man is called to be a streetsweeper, he should sweep streets even as Michelangelo painted, as Beethoven composed music, as Shakespeare wrote poetry.” – Martin Luther King Jr.

Frequently, I have heard the lament that “Humans are the only animals that have to work.” And while I understand the underlying sentiment and the frustration that goes along with it, I would say that all animals must work in order to live. It is only that the work of the animals is hardly recognizable to us as work because it is so engrained in their nature. When we see a bird collecting worms or making a nest, we do not say to ourselves, “Look at that robin, hard at work.”

Our goodwork should resemble something like this. It should be so tightly woven into our nature that onlookers should be curious as to whether or not it is actually work at all. Our work should not be something we ‘go to’ but something that comes from us. I have never liked the term ‘work-life balance’ and would instead like to strive for ‘work-life integration’, in which my work and my life are harmoniously joined together rather than demanding portions of myself be doled out equally.

Goodwork Involves the Whole Person

Part of the frustration in the work that humans have come to do is that it has become highly specialized, fragmented, and noncreative. For example, I had a highly specialized job once packing medical materials. I stood on one spot by a conveyor belt and would place one alcohol swab in the plastic pack as it passed by my station. That is all I did for eight hours a day.

By fragmented and noncreative, I simply mean that the work is separated from any satisfaction that could be earned from an end product. It does not satisfy our need for creativity because nothing ever comes to fruition under our watch in these deadend jobs, we only contribute our small part and then clock out.

In an ideal goodwork, one would find a path toward personal growth and self development. This would be part of the process that Carl Jung called ‘individuation’, or becoming yourself. Our work reflects this pattern, and if we are allowed to be creative, and to follow our work to the satisfaction of its end result, we can more earnestly develop our unique purpose.

Some specialization always takes place but it keeps in line with the development of skill, craft, and engagement rather than disengagement or fragmented roles. I was tempted to say ‘repetition’ as an aspect of highly specialized work but I find that goodwork can be equally repetitive, though this may occur in a way that is satisfying rather than demoralizing.

Our jobs have also become much more sedentary as they have become more about information and processes that demand we be more cerebral. This has led to an unsurprising decline in health. Our bodies and minds are most healthy when they are deeply involved in movement and engagement.

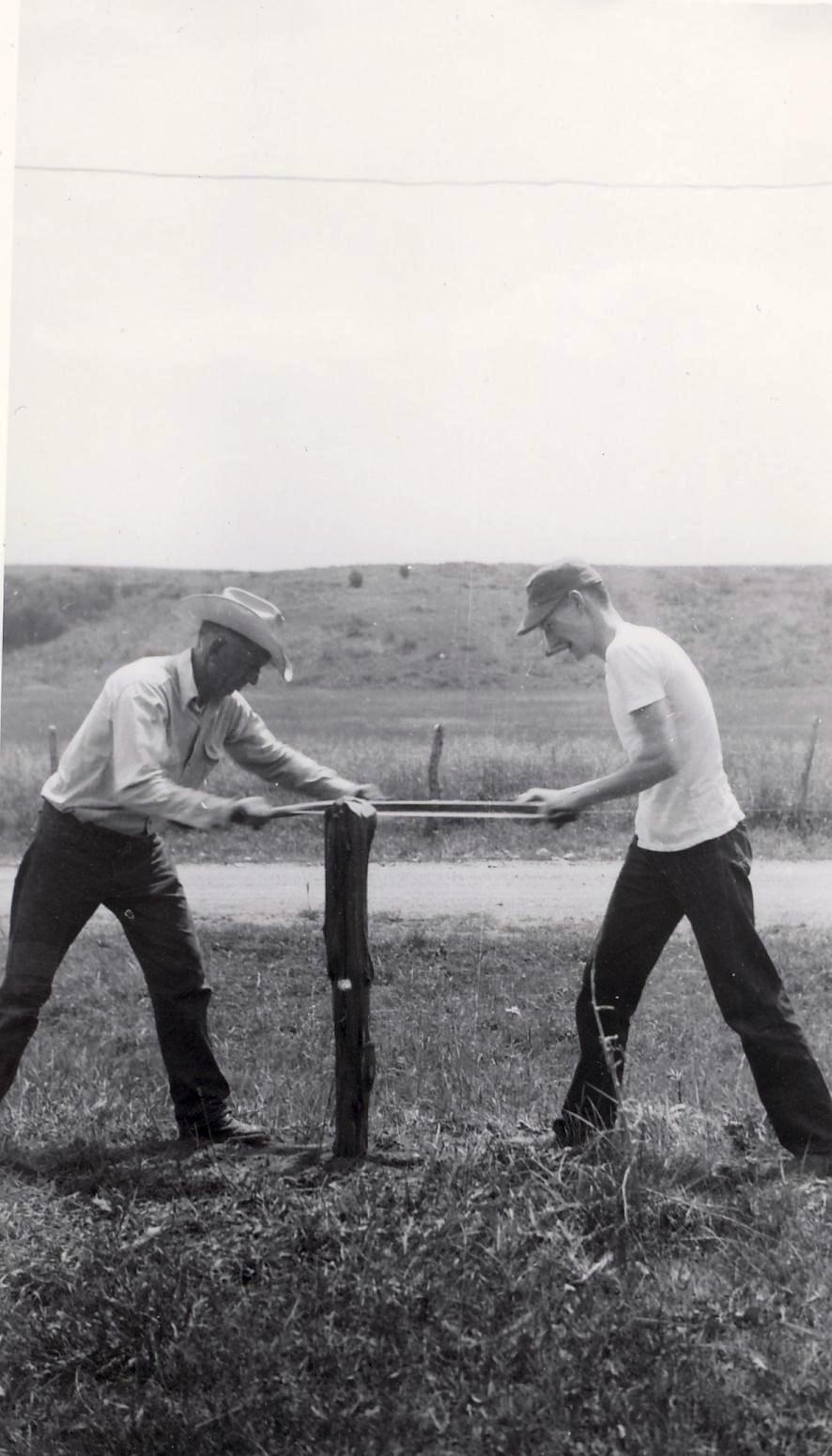

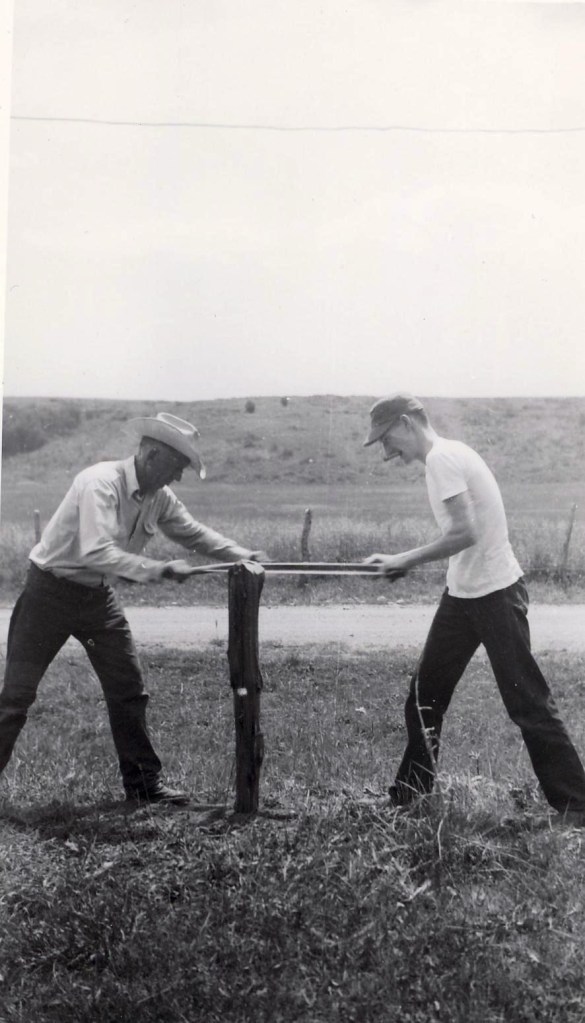

We are at our best when we are kept active in body, mind, and soul. Finding our goodwork means finding something that contributes to our mental and physical health as we attend to our duties. When I am attending to my farm and garden chores, I am using the muscles of my legs, back, shoulders. I get good exercise hefting feed bags or digging garden beds. My mind is engaged in planning projects, schedules, and organizing resources to fulfill the needs of my customers. These are just simple examples but one can see how such work can be fulfilling and engaging rather than stifling or overly monotonous.

Goodwork is Peaceful, Voluntary, and Contented

In this way, goodwork does not resemble the modern ‘hustle culture’ that you see online. Hustle culture asks you to just grind and hustle no matter the idea, the method, or the outcome. This kind of senseless frenzy may sound appealing at first but it is soon found to be exhausting, self-defeating, and empty. If you do not care what you are hustling for, what will you care when you achieve it? Don’t get me wrong, I believe in working hard, in self-discipline, and pursuing and achieving goals. But the way of the hustle is typically smoke-in-mirrors, empty promises, and multi-level marketing schemes that sell a dream rather than provide tangible value.

Goodwork, then, sets itself apart from hustle philosophies and aligns itself more with conscientious, consistent work that builds upon itself until it compounds into something valuable and sustainable, providing meaningful work and wealth for generations rather than a flash in the pan windfall that the grind promises.

Those involved in pursuing their goodwork are able to look their customers in the eye when it comes to upholding quality and consistency and these people often want to engage with their client base or community in long term relationships. Steady gain paired with consistent quality, all made possible by the principles outlined here, mean strong and resilient businesses and communities founded on mutual trust.

When I say peaceful, I mean goodwork lacks much of the self-imposed stress that follows from meaningless grind and hustle culture allure. When I say voluntary, I mean customers know exactly what they are getting and from whom they are getting it, and the producers know exactly what they are producing and go to great lengths to be the best to offer their product. When I say contented, I do not mean complacent. I mean that the work is not filled with a desperate dash for validation or recognition but is allowed to unfold with the dedication necessary for a long-lasting enterprise worthy of respect. If you have aspirations of becoming the biggest, you may not be the best when you get there. If you aspire to be the best, you may become bigger than you ever thought possible. When you get there you will be able to stand by your systems with pride and confidence.

Goodwork is About Connection

As someone who has worked in many different roles and in different trades, I believe that our work is important and can be approached in a positive and healthy way, regardless of what we may be led to believe. I want to share my work with the world and I want the world to share its work with me. If I could be so bold, I would love to help others find their goodwork and help them to put their corner of the universe in order.

“No matter how isolated you are and how lonely you feel, if you do your work truly and conscientiously, unknown friends will come and seek you.” – Carl Jung

Like nodes in a network, we connect and spread the information we need to grow in every way. The information I seek to discuss and share through this medium is not new or unique but it is my duty to pass along all useful experience to my network.

My goodwork is Goodwork. Through this blog and other written works going forward, I want to discuss relationships with work, wealth, and nature. I am not an expert in any of these areas. These writings are about musings, discussion, and progress. Perhaps more than its fair share of daydreaming. I draw on the wisdom and practicality of dozens, if not hundreds, of people that came before me and are much more articulate and qualified than I am. The areas I enjoy exploring – gardening, psychology, soil science, history, economics, bugs, personal finance – have been around much longer than I have. I have no illusions of adding any remarkable insights into these things but wish to provide a field guide in order to explore them more easily. I want to synthesize the widespread information that others have made the effort to pass along. I hope I can present this information in a way that each person finds something relevant to themselves and their life’s journey.